Michael Whelan

behaviour driven blog

Refactoring Kata

I recently came across a blog post from a couple of years ago where Scott Allen provided some gnarly code on GitHub as a refactoring kata exercise. Here is the background he provided in that post:

The bad news is the code is hard to read. Some might say it's intentionally obfuscated, but let's not assume malice right away.

The good news is there are six working unit tests for the code.

There are two goals to the exercise. One goal is to give developers an opportunity to practice refactoring (a Kata, if you will). The way I'd attack the code is to start with some renaming operations, then extract some methods, then perhaps break down the one big class or eliminate a switch statement using patterns. There is no perfect answer.

The larger goal is to convince anyone not entirely sold on the benefit of automated tests how tests can empower them to work with, experiment with, and change existing code - even code they don't completely understand. Although this code was intentionally obfuscated, it's not unlike walking into the code for a complex domain the first time and not understanding why a wurgled customer can blargsmack on Tuesdays if they hold a vorkenhosen status. All domains are nonsense at the start.

With one eye on Holland's 5-1 thrashing of Spain in the World Cup, I thought this might be quite an interesting exercise to try. I'm mindful that this could be quite a difficult post to read if I put too much code in, so I will try to limit my discussion to a few key points. The code will be on GitHub if you are interested enough to explore it further.

The Problem

There are four classes. Here is the main one, named Finder, which gives us the first clue that this is a searching algorithm. The code provides very few clues as to what it is doing though. Variable names, in particular, do seem to almost be intentionally obfuscated. The other 3 classes, are F, FT, and Thing! There is a nested loop, with those famous loop variables i and j, and it finishes up with a switch statement.

public class Finder

{

private readonly List<Thing> _p;

public Finder(List<Thing> p)

{

_p = p;

}

public F Find(FT ft)

{

var tr = new List<F>();

for(var i = 0; i < _p.Count - 1; i++)

{

for(var j = i + 1; j < _p.Count; j++)

{

var r = new F();

if(_p[i].BirthDate < _p[j].BirthDate)

{

r.P1 = _p[i];

r.P2 = _p[j];

}

else

{

r.P1 = _p[j];

r.P2 = _p[i];

}

r.D = r.P2.BirthDate - r.P1.BirthDate;

tr.Add(r);

}

}

if(tr.Count < 1)

{

return new F();

}

F answer = tr[0];

foreach(var result in tr)

{

switch(ft)

{

case FT.One:

if(result.D < answer.D)

{

answer = result;

}

break;

case FT.Two:

if(result.D > answer.D)

{

answer = result;

}

break;

}

}

return answer;

}

}

Renaming classes, methods and variables

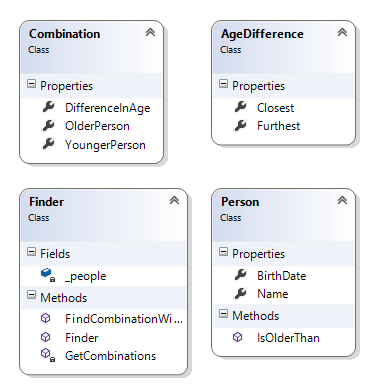

So, the first goal of the refactoring was to play detective and try to figure out what each variable and class did and then provide it with a meaningful name that added clarity. I eventually concluded that the algorithm was trying to find the combinations of two people, from a given collection of people, that were either closest in age or furthest apart in age. I definitely could be wrong on that though! Here is the model I came up with:

It turns out a Thing is a Person! A Combination is returned from the Find method and consists of a pair of people and their age difference. AgeDifference is an enum that is passed to the Find method and specifies whether the search should be for the pair with the closest ages or the furthest apart ages.

Newspaper Headlines

When I come across one big method like this Find method, the first refactoring I like to do is to break its logic down into steps, and then put each step into its own method. Each method should have a meaningful name that explains what it does. Then when you read it, each method call is like a newspaper headline. If you want to know more, you navigate to that method, just as you would with a newspaper story.

public class Finder

{

private readonly List<Person> _people;

public Finder(List<Person> people)

{

_people = people;

}

public Combination FindCombinationWith(IAgeStrategy ageStrategy)

{

var candidates = GetPossibleCombinations();

return ChooseBestCombinationFrom(candidates, ageStrategy);

}

private Combination ChooseBestCombinationFrom(List<Combination> candidates, IAgeStrategy ageStrategy) {...}

private List<Combination> GetPossibleCombinations() {...}

}

Now, hopefully, it should be very clear to anyone reading the code for the first time exactly what is happening.

Search Strategy

The switch statement checks the value of the enum passed in and uses different logic to compare two combinations. This problem is better solved with the strategy pattern. The consumer of the class can pass in a strategy class that actually performs the matching logic, which is much more extensible for adding new strategies in the future:

public interface IAgeStrategy

{

bool IsMatch(Combination first, Combination second);

}

public class ClosestAgeStrategy : IAgeStrategy

{

public bool IsMatch(Combination first, Combination second)

{

return first.DifferenceInAge < second.DifferenceInAge;

}

}

public class FurtherAgeStrategy : IAgeStrategy

{

public bool IsMatch(Combination first, Combination second)

{

return first.DifferenceInAge > second.DifferenceInAge;

}

}

I learned something interesting doing this exercise too. Because I was constantly running the tests after each refactor, I was trying to take small steps without jumping ahead and breaking everything. This led me to replace the enum with a factory class that had the same signature, and prevented all the tests from breaking. So, this enum:

public enum AgeDifference

{

Closest,

Furthest

}

became this factory class, generating each strategy:

public class AgeDifference

{

public static IAgeStrategy Closest

{

get

{

return new ClosestAgeStrategy();

}

}

public static IAgeStrategy Furthest

{

get

{

return new FurtherAgeStrategy();

}

}

}

I would normally have just let each consumer of the class pass new FurtherAgeStrategy() in for the method parameter, and would not have considered writing a factory. I'm not sure that a factory is warranted here, but it was interesting to discover the design opportunity during this refactoring, protected by a solid suite of tests.

Conclusion

I am a big fan of tests and the confidence they give you in refactoring. I was not in the target audience who needed convincing of this fact. But this sort of kata is interesting and useful to do. Thanks to Scott Allen for providing it!

I also refactored the tests a bit, to remove duplication. I won't bother to go into that here though. It's in the source code in my GitHub repo if you want to see it.

I think there's still quite a bit more refactoring to do. Any suggestions are welcome!